Step Into American Heritage With The Seager x Justin Trailboss Boot

Mar 12, 2026Life Lessons of an 81-Year-Old Men’s Mental Health Maverick

- Jan 5, 2025

- 0 Comments

939

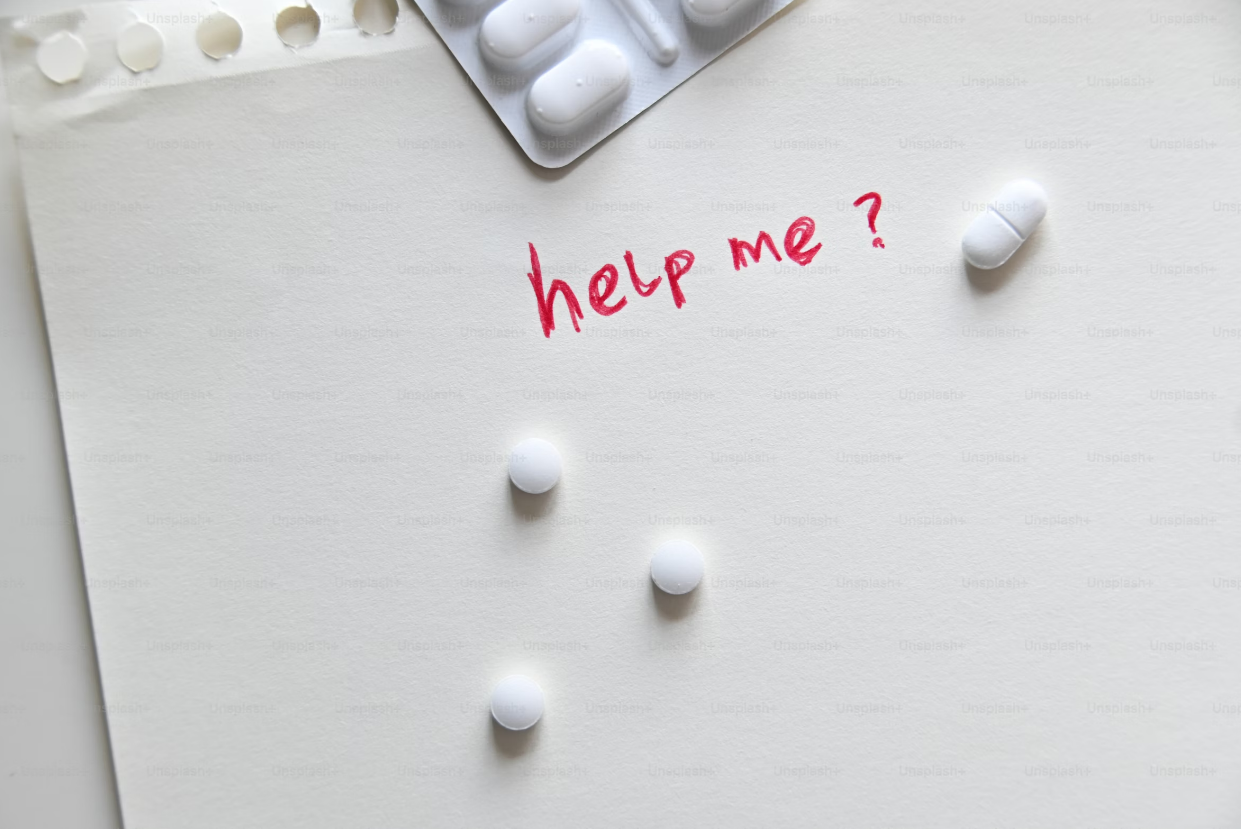

Part 5: Our Home Attracted Death Like a Magnet

Our home attracted death like a magnet. In 1949, the same year my father was committed to Camarillo State Hospital, Holly, a close friend of the family, shot himself. I remember going to the service, confused and afraid, but no one talked about why he died. Yet, everyone knew it was suicide. Years later I was looking through our attic and found nine of my father’s journals written between 1946 and 1949. They were a goldmine for me, giving me insight and understanding about my father’s inner world, his hopes, dreams, and the demons of doubt he wrestled with all his life.

There were numerous entries about his friend Holly, a fellow writer, written three years before the death. He described the pressures Holly was facing in the years leading to his suicide.

“When a theme possesses you the way Holly’s theme possessed him, good writing must result. You begin to see and understand what a herculean job novel writing is, how much guts, stamina, endless sweat and stick-to-itiveness you need.”

My father also felt the same force driving Holly to despair.

“How alike Holly and I are in our basic situation in life. We both struggle trying to make a living, feeling a furious hate inside, the hot breath of necessity blaring down our necks, the constant finger about to stick itself in our noses and telling us ‘times up. It’s too late.’ Now you’ll have to make it by working at what you loathe. The hands of the clock point to twelve.”

The same year that Holly died, my closest friend, Woody, drowned in the river near our house. He was my best friend and his sudden death left me feeling sad and lonely. I tried talking to my mother about my feelings, but she was caught up in her own fears. “Oh my God, I’m so glad you didn’t go with him to the river,” my mother said as she hugged me tight. “That could have been you.” I put my own feelings aside and tried to assure her that I was O.K. and wouldn’t go near the river.

My mother was preoccupied with her own death. From the time I was born, when she was thirty-five, I knew my mother was about to die. She talked about it all the time. “I just hope I’m around to see you off to high school,” she would tell me. Her voice was always light and breezy, but it chilled me to the bone. When she was still around when I went to high school, she wasn’t reassured, she just moved her imminent death a little farther down the line. “I just want to see you go to college before I die,” she would tell me.

I was seven when the “Forester man” came for a visit. He sold life insurance, but his story made it seem that he was here to offer protection and support. Though we had little money for essentials, my mother bought the whole package. My mother signed up for insurance on herself, so I’d be taken care of when she died. She also bought an insurance policy on me because “it’s never too early to think about your wife and kids.” As a dutiful son, I felt proud to own an insurance policy to take care of my family when I died…while I was still in the first grade.

I began to see death as a companion, a deadly twin that shadowed my dreams. I slept alone and had developed a ritual to enable me to go to sleep. I had to arrange the sheets and blankets in such a way that I created a safe cocoon and when it was just right I could fall asleep. But every night I would have the same dream:

I awaken and get out of bed. I walk from my bedroom into the dining room and from there into the kitchen and the living room. Somewhere along the way a dark figure jumps out carrying a long knife. I immediately begin to run away. I know if I can get back to my bed, I’ll be safe. But I never make it. I’m stabbed and wake up screaming.

My mother never seemed to hear the screams and I didn’t want to worry her. When I finally told her the dream she offered no clue of the cause, nor did she seem concerned. The dreams continued, but I never discussed them with her or anyone. Yet, my own preoccupation with death took hold in my subconscious, only to surface many years later in college. I took my girlfriend to see the play “A Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical masterpiece about growing up in a crazy, dysfunctional family. My girlfriend hated it. I felt I had found a kindred spirit who was telling my story. One small section spoke deeply about my own life to that point.

In the play, as his family unravels around him, the younger son, Edmund, tries to make sense of his place in the family drama. He says:

“It was a great mistake, my being born a man, I would have been much more successful as a sea gull or a fish. As it is, I will always be a stranger who never feels at home, who does not really want and is not really wanted, who can never belong, and who must always be a little in love with death!”

After I stopped visiting my father in Camarillo, my mother and I never talked about him. It was as though he was dead or had never existed. We became a family of two. My mother never mentioned him and I told kids in school that “my father died,” which got me a little sympathy that I never got when I said he had a “nervous breakdown and was in a mental hospital.”

Life Lesson: When adults deny the reality of depression and suicide children are left to grapple with their confused feelings alone.

When my mid-life father took an overdose of sleeping pills and was committed to the state mental hospital the adults in my life couldn’t deal with the reality of his feelings of despair. My mother was consumed by her own terrors and denial and chose not to visit him in the hospital. She tasked my uncle and me to make the weekly visits to see my father. Family and friends didn’t talk openly about the death by suicide of my father’s close friend, Holly, another struggling creative artist.

Men die by suicide at rates four times higher than the rates for females and is even higher as men get older. When we deny our early wounding, it often turns into depression, which can lead to suicide.

Life Lesson: Although depression and despair that can lead to suicide can impact everyone, it is more prevalent among sensitive, creative, men and women.

Kay Redfield Jamison is Professor of Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. She is the co-author of the standard medical text on bipolar disorder and the author of national best sellers An Unquiet Mind: Memoir of Moods and Madness, Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide, and other books.

In Touched with Fire, she begins by quoting poet Lord Byron as he talks about himself and other creative types.

“We of the craft are all crazy,”

said Byron about himself and other creatives.

“Some are affected by gaiety, others by melancholy, but all are more or less touched.”

Where has depression shown up in your life or in the lives of people you love? Do you consider yourself a creative person? Do you see a connection between your creativity and times you felt down or depressed?

I look forward to hearing from you. New training opportunities coming in 2025. Drop me a note to [email protected] if interested.

If you appreciate these articles, please share them. They are my labor of love. If you are not already a subscriber, feel free to do so here.

Publisher: Source link