The Billionaire Clobber Revolution – Why the Men Are Boring and the Riviera Is Blooming

Jul 3, 2025How much do you actually know? An interview with Alan Flusser – Permanent Style

- Aug 4, 2023

- 0 Comments

265

By Manish Puri

A few months ago I had the privilege of speaking with Alan Flusser about the history of New York bespoke tailoring.

From the opening beats of our conversation it was clear that Alan wasn’t about to be constrained by the narrow parameters of my article. How can one speak about New York tailoring without benchmarking it against the best of Savile Row? How can one appreciate New York tailors without acknowledging the Italian traditions that many of them were raised in? Why should Alan survey the scene without contextualising his unique place within it?

So, across more than two hours of charming conversation (pausing only at the behest of Zoom Basic’s time limit), Alan and I spoke about a variety of subjects that spanned his career in menswear. And I thought it was a shame so many didn’t make it into that NY bespoke article.

So here I’ve included some highlights of our discussion, including several themes that I think would be of interest to Permanent Style readers: wearing unstructured tailoring, learning to dress well, the differences between Savile Row and tailors in the US, and some fascinating insights into the sartorial importance and cultural impact of the colour pink (which I wrote about a few months ago).

But first, we began with a brief history of Alan’s first taste of buying custom/bespoke clothing.

On his introduction to custom

I ended up having my clothes custom made for me since I was 17 years old, though it was not by design, no pun intended. My girlfriend’s father was a self-made real estate guy and he needed his clothes made because he was big. After seeing that I was very interested in these things, he said to me, “Why don’t you come to the tailor and just help me pick out clothes?” So, long story short, I did that.

He liked the results, and was always very entrepreneurial, so he said “I have three or four friends who can afford to go to tailors. You could take them, advise them, and they could pay you a commission, and you could get a commission from the tailor,” which I thought was a great idea.

So I started doing that, and I told the tailor, instead of you paying me a commission, why don’t you just give me credit towards clothes, and I’ll make clothes as we go along. So from the age of 17 or so, I would go to a tailor and I was interested in having him help me become the best-dressed person I could be.

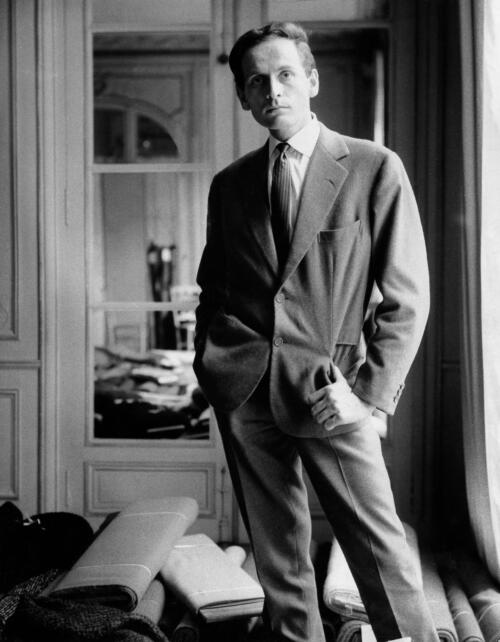

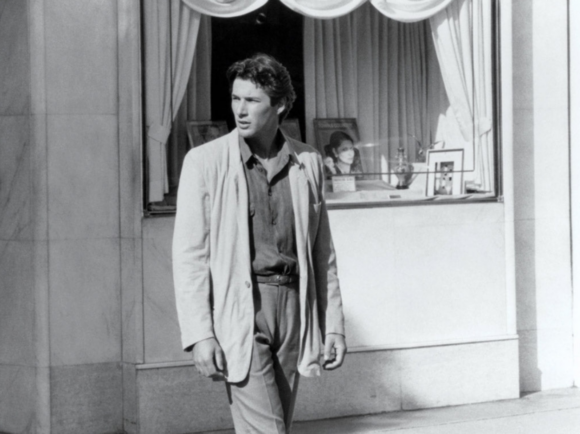

When I went for my first important job interview for Pierre Cardin (above), I brought four or five of the garments I had made for myself to show them. I guess they thought they were sufficiently interesting enough to qualify, and I kind of started my real career.

On visiting the UK

I was making clothes in England in the Cardin era. I was going to Scotland and to Shetland and to different places. We really took advantage of what England had to offer. Ralph and I are the ones who went to these places, took these old mills and had them make new things for America. So, I spent a lot of time in the UK, and was having clothes made there.

I stayed at all the hotels, and I finally decided Claridge’s was my favourite because it was easier to get in than the Connaught. Every time I came downstairs to have a drink, they would play some American tune – on cue.

On Savile Row compared to America

Savile Row is the most unique collection of tailoring people in the world. You have all these tailors, and they have their own house look, and that’s how they’ve survived. In an English suit you’re going to get into less trouble because they have a house style, and it’s something you can judge upfront.

There’s also much more of a uniformity. Of course, there’s differences in subtleties between Huntsman and Poole and Anderson and Sheppard and Davies. But from 10 feet, they could look similar.

In America, tailors came into being because they made something that was different from everyone else – it was much more distinct. The tailoring represented more of a lifestyle.

And because we don’t tend to have a house style, and people need business, they’re apt to make more stuff that caters to what people want to have. In America, it’s very dangerous when someone says, “I’m going to make whatever you want”. You’re really in a lot of trouble. It means you are now the designer, and it’s going to live or die based on what you tell the tailor.

Plus, with England, along with the actual making of the clothes, you tend to get more information about tastes and style, even if it’s more conventional, than you would in America – where at this point, very few have any real background with regards to the history of clothes or what differentiates the twenties or thirties from the fifties.

There’s more of a continuum with each tailor in London. You’ll get to see how the English are putting together ties and shirts with suits, and you’re more apt to learn something about the skill of it, because it is a skill.

Savile Row is still a little bit of an oasis of learning in that sense – one place that you can get to understand what you look good in and why. There are so few places like that now. America’s not as tradition bent, and today it’s even less so – it’s more like, “well, what are you making now?”

On pink

How could you have ever known [when writing an article on pink] that you picked up a sartorial poker, whose cultural origins and social impact transcend not just some coded gender identity, but the American soft-shoulder sensibility becoming known as Ivy League.

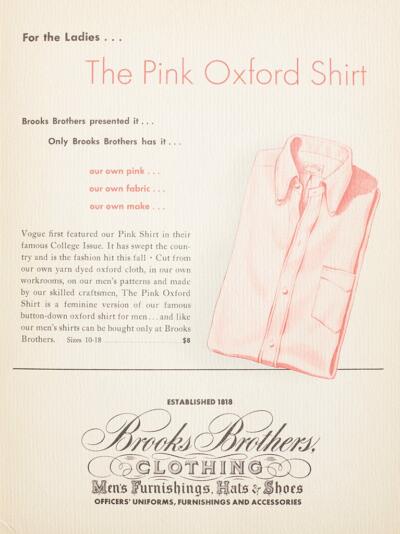

Unfortunately I don’t have the time or scholarship at hand to elaborate on the referenced wearable – that being the original Brook Brothers pink oxford button-down. However, make no mistake, this article of attire is inextricably tied up with the elitism, tradition, and even sexual coming of age of the period. A creation of Brooks Brothers, they turned its ownership into one of the Ivy League’s standards and an obligatory rite of membership.

I’ll just point you to a 1949 Vogue and Brooks Brothers woman’s advertisement (above) that sanctioned the pink male classic for the opposite sex, that also happened to spearhead the first Brook Brothers women’s collection. (The model above is also wearing a Brooks Brother Oxford shirt for the 1949 Vogue College issue).

Once the beachhead of pink for men had been forged, other pastel garments awaited, followed by the country’s increasingly sportswear-driven fashions, including golf-course brights and all measure of high-colour nautical blues for island and water life.

Palm Beach became America’s most important sportswear breeding ground, and in America’s menswear industry the pioneer for at-play sportswear, which included more colour in menswear than had ever been seen.

The real story of pink and its outsize impact on colour in menswear is probably one that will never been written, yet it is well-documented in the fashion pages of the early Apparel Arts and Esquire magazines.

So…pink is pretty much a uniquely American tale. But fortunately, it’s one that I can still enjoy, recollecting my clothes-conscious father attired in one of his ‘346’ Brooks grey-flannel lounge suits, obligatory Brooks pink BD, black ground club tie, and shod in pink hose and black tassel slip-ons. Astaire never danced too far from his sartorial reveries.

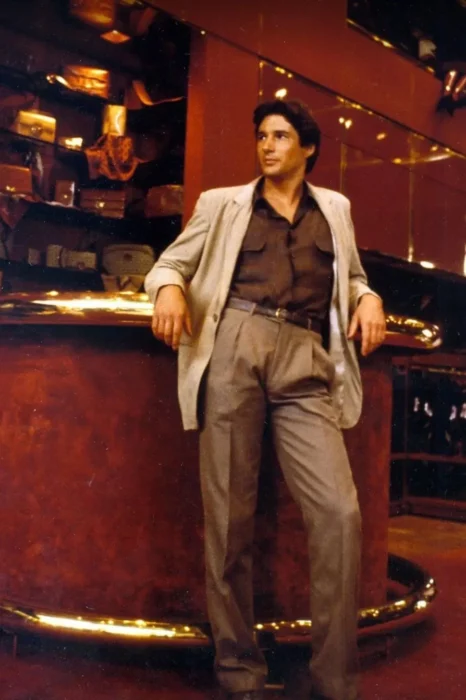

On unconstructed tailoring

The thing about America that makes us unusual is that we invented sportswear. We know how to appreciate soft, unconstructed, comfortable clothes. We are the country of comfort.

There were lots of obstacles to unconstructed tailoring, but we’ve been moving towards it inevitably, and COVID has done more to advance it than anything. Since the eighties, every good retailer in the United States has carried some kind of unconstructed clothes and tried to get his customer to understand it three or four different times.

That came very slowly, because it was always more expensive. The term unconstructed denoted to people, “Oh, this is less expensive”. No, it is actually more expensive, because you have no linings covering everything up so the tailoring has to be very, very good.

And there wasn’t a whole lot of makers of soft clothes outside of Italy. Because it takes more than just tailoring skills – it takes people who have a sense of style and understand what’s going on in fashion, and how to translate that into their own work.

Plus, when you’re talking about the attitude of unconstructed dressing, it’s a lot more difficult to teach because you don’t have the structure to hold it in place. A suit was always the easiest of things for a man to wear. Anybody can put on a blue suit and a white shirt and some tie that matches – that’s really easy.

But if you’re asking someone to, all of a sudden, wear an unconstructed blue blazer and let’s say a grey pair of pants, and now the shirt, what are we doing with the shirt? What kind of collar? Tie? Am I wearing a pocket handkerchief? I mean, it’s asking a man to do much more. That’s a whole ‘nother void, so to speak.

We don’t have people that can teach how to dress at retail. We used to, but this is an education, an illumination of the idea of wearing something that looks similar to what you are accustomed to seeing on someone from the outside, but feels totally different. And you wear it totally differently.

On fashion vs permanent style

The issue with, let’s say Armani, was that one year you had low gorge, wide shoulder clothing, long – and the next you had rounder shoulder, tubular looking clothes. All of the previous ones were obsolescent. The great majority of fashion sold in the seventies and eighties and nineties is obsolescent.

That’s one of the reasons of Ralph Lauren’s success – he has a higher percentage of clothes that don’t become prematurely obsolete than any other designer in the world. And that must resonate with people.

I think that plays a big role in terms of Simon’s idea of permanent style. Things that transcend the moment – and for people to be able to distinguish that requires some education on their part.

On learning to dress well

Being able to learn how to dress well isn’t that complicated.

I mean people have to know what colours flatter them the most and why; what proportions flatter their individual physique and why. And that’s actually what’s difficult about it – getting the right information.

What’s easy about it is the fact that it’s finite. In other words, the width of your shoulders is not changing. The size and shape of your head is not changing. It’s just that it’s very difficult to get the right information for each individual person.

That’s why our shop, I think, has all these years behind it. I say to customers, it doesn’t cost us any more to give you the right information than the wrong information. It doesn’t cost us any more to make something fit you properly, than not fit you properly. But what goes into it is an awful lot of knowledge. And, to a certain degree, that’s what dressing is about, how much do you actually know?

Manish is @The_Daily_Mirror on Instagram

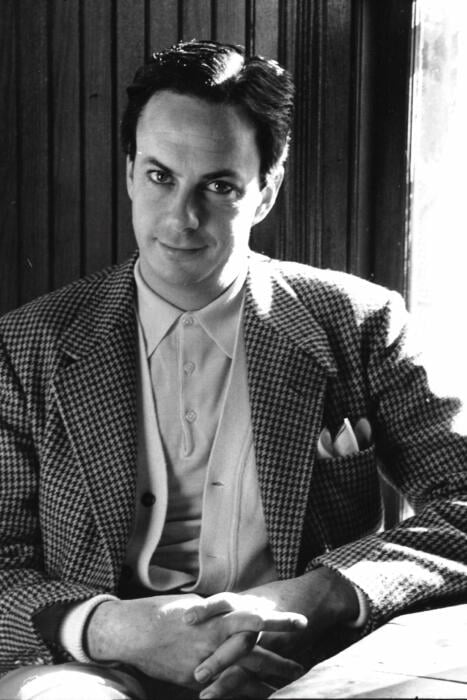

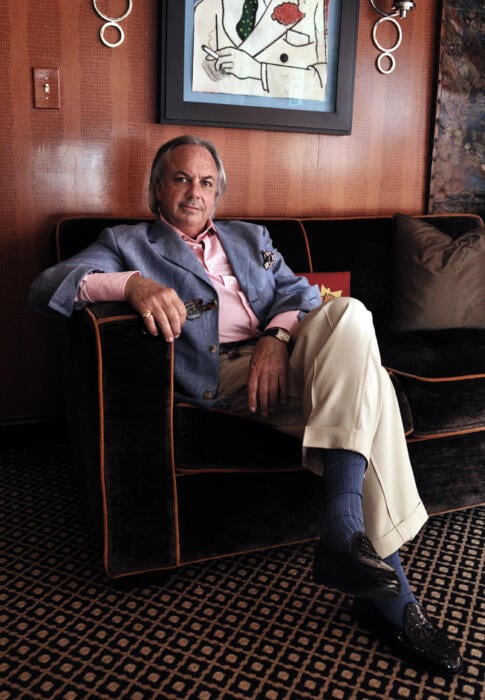

Images of Alan courtesy of Alan Flusser Custom

Publisher: Source link