Horace Skincare Review: Why Horace Is Dominating The Modern Man’s Bathroom Cabinet

Feb 21, 2026How a cape is made – and would I wear one? – Permanent Style

- Jul 15, 2024

- 0 Comments

354

By Manish Puri.

During a recent trip to Madrid, I paid a visit to Casa Seseña, run by Marcos Seseña (the fourth generation of the family), and one of the few shops in the world still dedicated to making capes. In part one, I covered their 123 year-old history. In today’s article, I take a look at how their capes are made and who’s buying them.

–

The traditional capa española is made from fine merino wool – a commodity fiercely guarded by the Spanish until the 18th century (any attempt to export merino sheep before then was punishable by death).

When Seseña first opened in 1901, the wool they used to make their capes was sourced from flocks in the Salamanca region. However, these days half the raw wool is Spanish and the other half Australian. From there it’s sent to the Spanish mountain town of Béjar where it is woven, dyed and, most critically, washed…a lot.

The mineral qualities of the local water accentuate the softness of the material, while the multiple washes (which cause the wool to shrink in size by half!) permits a denser weave – which helps the cape retain its shape and is key to thwarting cold air and rain showers.

As an aside, the significance of the textile industry in Spain’s Golden Age was underlined some days later when I visited another Madrid institution, the glorious Prado museum, where two of their most famous works caught my attention (above).

The first was Agnus Dei, completed between 1635 and 1640 by the Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán, where a trussed lamb evokes The Passion – the lamb depicted being a merino.

The second was Las Hilanderas (or The Spinners), painted around 1657 by Diego Velázquez, where a group of women are shown spinning wool at the Tapestry Workshop of the Monastery of Santa Isabel in Madrid.

Once the finished wool reaches Seseña, it’s cut in the back of the shop by cutter Carmen Fábrega who has been with the business for 17 years (above, working on a paisley design for a women’s model).

Their signature 1901 cape (laid out on the floor below) requires five metres of a single length of wool cut into an elliptical shape – not a circle, as some would have you believe, otherwise the hem of the cape wouldn’t hang at the same level all the way around the body.

At the front of the cape, the insides are partially lined (embozo) with cotton velvet which adds contrast to the (typically) black cloth, and offers an extra layer of protection for the face when the cape is swept up and across the shoulders. At the rear is a vent (escusón) which allows the wearer to gather the cape in front of them before taking a seat.

While all the finishing is done by hand (taking around 10 hours per cape), the hems are left raw (above), another byproduct of using such a dense wool.

The 1901 model comes with an esclavina – a topstitched shoulder cape that gives yet more protection from the elements – and is finished with a silver ‘charro’ clasp made in Salamanca (below).

While the clasp could, in theory, be used to fasten the cape, its presence here is purely ornamental. The need to secure the cape obviated by its sheer weight – typically around 5-6 kg, so if worn correctly it won’t be slipping off your shoulders any time soon.

With that in mind, Marcos took great joy in showing me how to properly don the cape. I won’t describe the process here (there’s a jazzy video online that does that), but I will say there was a pleasure and mindfulness that came from having to focus on putting on and setting a garment just so – a far cry from the passivity of ‘chucking on a hoodie’.

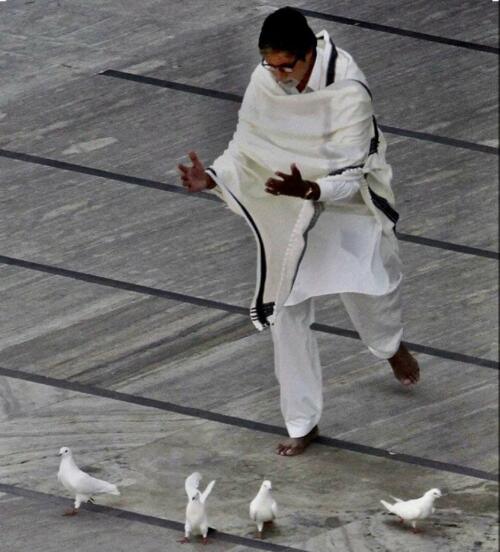

And, once the cape was swept over me, I realised that (weight and length aside) it isn’t entirely dissimilar to an Asian shawl (as seen below on Indian actor, Amitabh Bachchan) – which made the garment a little more familiar and less intimidating.

The standard length of a cape is 110cm, which should work for anyone around 175-180cm tall (5’ 8” to 5’ 11” in old money). However, as this is a handmade product, bespoke orders are common, with most customers adjusting the neck size and/or length. The RTW 1901 cape is €1100, and the Alfonso cape (which is less embellished as it comes without the esclavina and the silver clasp) is €1000. Bespoke prices start at €2000, and, depending on the design and season, orders take around a month to fulfil.

I chatted with Marcos (above) about his customers and was told they tend to be aged 35 and upwards – with a two-thirds/one-third split between international and domestic, and customers from the US making up 75% of the international orders.

Among the local buyers, Marcos touched on an attitude when wearing capes – a comfort with “standing out” and “being admired”. It’s a comment that stayed with me during my stay in Madrid – particularly in the well-heeled barrios where I spotted a number of elegant and sharply attired men. (And it’s something I’ll revisit in an article on Spanish style.)

Purchases are often intended for special events: weddings, parties, fashion weeks and even Royal or Presidential gifts. Marcos added that the common thread between his customers was that they were “people who appreciate the elegance and the handcraft of the cape”.

I also spoke with my friend Linus Chu, who I’ve seen on a few occasions sporting a beautiful velvet cape he designed for his brand The Sustainable Man (above in an image taken by Mohan Singh).

“Most people react quite positively given how minimalist it is. Sure, it’s a cape but it doesn’t have any ceremonial elements, so I think it can be complementary to everyday tailoring – my go-to is to wear it with a black turtleneck and a 4 x 1 DB. I also sometimes wear it over my charcoal and navy suits, which makes the look less businesslike. My rationale has always been that it’s the most ‘simple’ garment, it’s almost like coating yourself with a leaf.”

Linus’s allusion to Adam and Eve brought to mind something else that Marcos said about capes being “the first garment – an animal skin on your shoulders.”

Like Linus, I’d reluctantly eschew the more ornate capes (as beautiful as they are) for a simpler model like the Alfonso – as worn above by Steve Knorsch, the New York Managing Director of Cad & The Dandy.

If you ever try on a cape, the natural instinct is to rest it on your shoulders and stand stock-still like a petrified superhero – it’s not the best look. Indeed, if we tried on other garments with the same level of inertia we’d buy fewer clothes; but we do up a button, we stick a hand in a pocket, we pop a collar – anything to efface the novelty, to neutralise the ‘new car smell’.

Now, there are no buttons, pockets or shirt collars on a classic cape (unlike Marcos’s modern designs such as the Darcy), but you can animate the cape by enveloping yourself in it and letting it take some of your natural shape and posture – which I think is the most beautiful aspect of Brassaï’s photo of the two clergymen at the top of the article, and is exactly how Steve is wearing his. The cape will only look it’s best when one starts to ease into it and get comfortable.

Of course, to do so requires a little confidence and verve – as Marcos told me, “the cape cannot dominate you; you must dominate it”. If you can’t muster that, then it’s probably fair to say a cape isn’t for you.

I departed Casa Seseña, as I often do after visiting niche makers, filled with affection for the product, and an appreciation of the bloody-minded dedication that goes into keeping a business going when the prevailing winds of popular conventions are blowing so hard against you.

I didn’t leave with a cape this time, but I can say I no longer have cape fear.

Manish is @the_daily_mirror on Instagram

Publisher: Source link